Katie Scott-Marshall has an MA with Distinction in Modern and Contemporary Literature and a First Class BA Hons Degree in English Literature, both from Newcastle University. One of her research interests is the intersection between gender studies/ feminist theory and patriarchal traditions within Christianity, and her MA dissertation focused on the Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor and O’Connor’s usage of grotesquely gendered bodies.

When we think of Eve, the notorious ‘first’ female in the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible, we conjure up images of snakes, of forbidden fruit, and of the Garden of Eden. The story of Eve is undoubtedly one of the most well-known and familiar didactic narratives in the world: Adam and Eve, the first man and woman on Earth according to the creation story, happily resided in the Garden of Eden. God’s only request of them was that they were not to eat fruit from one of the trees, but Eve was tempted into doing so by a treacherous serpent, and shared the forbidden fruit with Adam. God punished them by expelling them from the Garden of Eden and condemning Eve to a lifetime of painful childbirth and subservience to her husband:

I will greatly increase your pangs in childbearing; |in pain you shall bring forth children | yet your desire shall be for your husband, | and he shall rule over you. (Holy Bible, Genesis, 3.16).

Eve became known as the source of Original Sin, responsible for the fall of mankind, and she became a blueprint figure for all subsequent women; the reason for their menstrual suffering, their pains during labour, and a cautionary tale as to why they should submit to their husbands. The prevalence of Judeo-Christian discourse in western culture has meant that the story of Adam and Eve has been enduring, and over two thousand years of cultural contributions to the figure of Eve across a range of traditions and disciplines means that a comprehensive biography would be impossible. My intention here, however, is not to recount the story of Eve, but to draw attention to her enduring reputation as a dangerous and overtly sexualised woman, even in the present day, and to raise the question of what Eve’s legacy means for modern women. Ultimately, Eve is just as relevant a figure as ever in womankind’s long historical struggle against patriarchal violence.

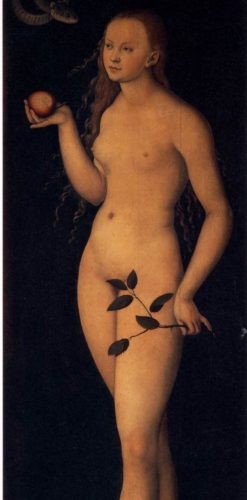

The story of Adam and Eve still permeates modern culture, and in particular the association of women with serpents endures in art, literature, and popular culture. Indeed, from Debra Paget’s erotic snake charming dance in Fritz Lang’s 1959 film The Indian Tomb to Britney Spears’s iconic performance with a live python on stage at the MTV Video Music Awards in 2001, the serpentine has long been inextricably linked with the feminine and more specifically, with female sexuality. A quick current day ‘Google image’ search of ‘snakes and women’ reveals thousands of sexualised images of women and snakes. The image is so ingrained and present – and commercialised – that it is even possible to buy a sticker of Eve and the serpent to be placed on a MacBook, Eve’s hand encircling the Apple logo. As recently as 2014, an advert for Airwaves chewing gum featured a man going back to a woman’s apartment expecting to spend the night but instead finding her bedroom to be full of snakes and fleeing in horror. The figure of Eve has a highly erotic and sexualised history in various art traditions, having been repeatedly depicted as nude and entwined with a serpent, particularly during the Renaissance period (see the title image for this post).

Throughout history the serpentine and the feminine have not only been associated, but even conflated, resulting in a number of depictions of the serpent as actually being gendered as female, and sometimes having a female face or breasts (see image 4). This conflation is quite transparent in its revelations about society’s perceptions of women: the creation story makes it abundantly clear that the snake is a seducer, a liar, a manipulator, and a hateful creature sent by the Devil. Take for example this passage from Ford Maddox Ford’s Parade’s End, a classic twentieth century modernist novel including an archetypal ‘dangerous woman’, the beautiful, selfish and sexually promiscuous temptress Sylvia Tietjens. Her husband imagines her:

[C]oiled up on a convent bed… Hating… Her certainly glorious hair all around her… Hating… Slowly and coldly… Like the head of a snake when you examined it… Eyes motionless, mouth closed tight… Looking away into the distance and hating…

This cold, negative portrayal of Sylvia as snake-like, ‘coiled up’ on a bed with ‘motionless’ eyes is telling in its association with monstrous femininity. The reader is aware of Sylvia’s feminine traits, such as her ‘glorious hair’, and Christian themes and sexual boundaries are hinted at in the inclusion of the ‘convent bed’. The image of the serpent is once again bound with the threat of female sexuality, in view of Sylvia’s sexual transgressions, but also with female deception.

The fall of Eve was often alluded to in Victorian literature, which was obsessed with ‘fallen women’ and the virgin/ whore dichotomy. Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1892), a famous novel chronicling the downfall of its working class female protagonist, Tess, is ripe with imagery and symbolism relating to Eve and the Garden of Eden. Her character is seduced (or more accurately, raped, although critical opinion differs and there is more than one version of the text), by Alec, a devilish sexual libertine, under a tree, mirroring the way Eve succumbs to temptation in the Garden of Eden. The name of the forest where this encounter takes place is ‘the Chase’, in a deliberate nod to the way in which Adam and Eve were chased from the Garden of Eden. The imagery of fruit is used to further consolidate Tess’s role as a kind of Eve, with Alec offering her strawberries at one point in the novel, which she accepts. The fallen woman appears as both a weak sinner, vulnerable to seduction, but also as an inadvertent temptress, a sinner of her own making. Franz von Stuck’s Victorian era painting of Eve, The Sin (1893) capitalises on the latter notion and depicts Eve as a dark and sensual woman who is fully complicit with the serpent (see image 6).

The Bible declares that Eve was made from the rib of Adam, to be his ‘helper’, and so she is often cited by traditionalists as evidence of God’s intentions for gender complementarianism, rather than full gender equality in terms of shared tasks and responsibilities. Complementarianism, the idea that men and women were created ‘equal but different’, and intended to take on different roles has been hotly disputed by feminists, theologians and scholars alike. In the Jewish book The Alphabet of Ben-Sira, an anonymous medieval text, Eve is Adam’s second wife, and his first is a woman named Lilith (see image 7).

Lilith refuses to sleep with or to submit to Adam, and when he attempts to coerce her into an inferior position, she voluntarily leaves Eden and engages in sexual relations with demons. God sends angels to her, who threaten to kill her new demonic offspring unless she returns to Adam. She refuses, and so God makes a second wife for Adam, Eve. Although this version is not commonly known, it is fascinating in its depiction of Lilith, a female figure who not only defies patriarchal order but also manages to evade the same punishment as Eve. Lilith’s rejection of complementarianism and Eve’s sentencing to a life of being ‘ruled over’ by her husband are still struggles that carry enormous relevance for modern day women, where women still take up the majority of caring roles and are often assumed to be primarily responsible for child-rearing. A huge number of contemporary feminist issues, including the objectification and sexualisation of women, equality for women in relationships and the workplace, rape culture, violence against women and the reproductive value assigned to women, all find origins in Biblical scripture, and in Genesis and the creation story in particular.

It might seem somewhat strange to be appreciative or even in admiration of Eve, given that patriarchal religious traditions so often cite her as the sole cause of all women’s woes and encourage us to blame her for them (and of course, for the majority of atheists, invented her entirely as an example of deviant womanhood in order provide justification for the oppression of women). Yet the figure of Eve, and perhaps even more so the figure of the lesser-known Lilith, are hugely significant in the patriarchy’s configuration of women as a threat in the first place. These are not women who submitted to their husband, or even to God. The enduring legacy of Eve is not that of original sin as we would be led to believe, but of the original dangerous woman. In view of society’s longstanding ill treatment of, abuse of, and discrimination against women, it is almost comforting for contemporary feminists to remember that the beginnings of patriarchal Judeo-Christian discourse on gender and sexuality started with a rebellious and transgressive woman.

Sources

Ford, Ford Maddox. Parade’s End (London: Penguin Classics, 2012).

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the d’Urbervilles (Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 2000).

The Holy Bible, New Revised Standard Version (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989).