Lynnda Wardle was born in Johannesburg and lives in Glasgow. She has a BAHons (Comp Lit) from the University of the Witwatersrand and a BA Community Development from Glasgow University. She received a Scottish Book Trust New Writer’s Award (2007) and has had pieces published in thi wurd, Gutter, New Writing Scotland and PENnings magazine. She is currently working on a memoir about growing up in South Africa. Find out more at www.lynndawardle.com

Lynnda Wardle was born in Johannesburg and lives in Glasgow. She has a BAHons (Comp Lit) from the University of the Witwatersrand and a BA Community Development from Glasgow University. She received a Scottish Book Trust New Writer’s Award (2007) and has had pieces published in thi wurd, Gutter, New Writing Scotland and PENnings magazine. She is currently working on a memoir about growing up in South Africa. Find out more at www.lynndawardle.com

We visited the Union Buildings in Pretoria, my father and I, usually on a Sunday. My mother packed us sandwiches and a Thermos flask of milky tea that tasted like sick. She didn’t come with us. Off you go, she’d say patting her hair; I have things to do. My father would drive up the steep access road and we’d be careful about selecting a parking space that gave the old white and grey Austin maximum shade cover. My father would spread a hand towel that he had cut and adapted to fit the dashboard in order to stop it cracking in the sun.

Pretoria shimmered on days like these; avenues blue with jacaranda trees in the heat haze. The Union Buildings are set far back from the road — two imposing sandstone arms encircling the green terraces below. Although we came here often, my father shared the same history lesson each time. He liked to point out the statue of the Boer general, Louis Botha, on his horse at the foot of the gardens. A great General, he would say, a true Afrikaner. Under the pine trees, people laid out their picnic blankets, children’s voices high above the roar of traffic. As we climbed the terraces, my father always a few steps ahead of me, I would not be thinking about history, or the Boer Wars or how the building was conceived as a compromise between Boer and Briton. This history lesson was familiar to me but the facts seemed irrelevant compared to the day; to the sun, to the heat, to the ice cream melting down my forearm and dripping raspberry drops into the red dust. The Boer War to my six and half year-old self was a faded black and white photo of men in ill-fitting suits and enormous dark beards standing next to women in long dresses and bonnets.

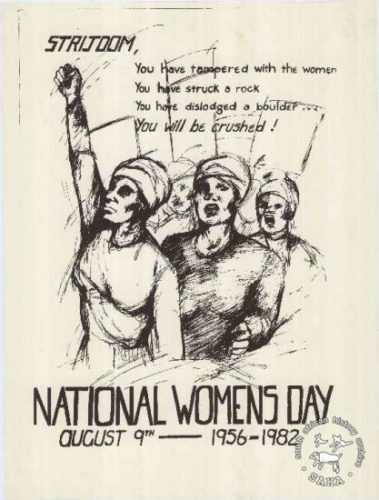

The history lesson my father never gave me on our visits there was that at this very place, in 1956, 20,000 women marched to protest against a decision to make them carry a Pass Book. Pass Laws were designed to control the movement of black people and were ultimately the legacy of slavery in the 1800s when the movement of slaves in the Cape Colony was controlled using identity documents. Although the system had been informally used since 1913 under the British to control the movement of blacks, by the early 1950s, the Nationalist government under the leadership of JG Strijdom, the ‘grand architect’ of apartheid, a new, more rigid system was instituted. Now all males over the age of 16 would be required to carry a Pass Book. This document contained both personal and employment history and had to be carried at all times. Failure to carry a pass would result in imprisonment. Women had not been included in this legislation, but in 1953 when the government decided to force women to carry Pass Books as well, there was a groundswell of resistance. Women knew that carrying a pass would not only severely limit their ability to move around for work but would also make it impossible to look after their families if they were imprisoned for the offence of not carrying a pass.

Four women mobilised support and organised the huge protest that was to take place on Augsut the 9th 1956 at the Union Buildings, the seat of the apartheid government. Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Jospeh, Radima Moosa and Sophie de Bruyn knew that this was a dangerous undertaking. As Sophie De Bruyn explained later in an interview ‘We entered the holy grail; it was like us being cheeky! We dared to enter their domain.’

All four knew that this political gathering could end in violence and bloodshed. However, they had all worked in the trade union movement and knew how to organise a large gathering. Black people were not allowed to gather publicly and so the women were told to make their way to the Union Buildings in small groups, careful not to appear to be marching. By late morning however, there were thousands of women gathered, many dressed in the green and gold of the ANC. Others were wrapped against the cold in brightly coloured blankets, carrying their own babies or the white children they were looking after, on their backs. Over again they sang:

Wathint’abafazi, wathint’imbokodo!

You have struck women; you have struck a rock!

The four organisers left the petitions against the Pass Laws signed by thousands of women in bundles at Strijdom’s door. He had not come to meet them and the rumour was that he was not even in the building. Lilian Ngoyi then led the women in half an hour of silence, symbolic of the silencing of women’s voices for decades under white rule.

To date this was the biggest mass gathering of women ever seen in South Africa. The campaign against Pass Laws for women continued for another seven years but increasing police intimidation, harassment and arrests eventually wore down resistance and black women were finally forced to carry passes (nicknamed ‘Dompas’ or stupid pass) in 1960. Their march in 1959 was one of unity and defiance in the face of injustice. The march has become a symbol for women who continue to fight for women’s rights in South Africa today.

Having reached the first green level, our backs to the buildings my father and I could survey the view across the city. The sprinklers spritzed the beds of bright vygies and strelitzias. Of course, there were no black people up here, other than a few of the gardeners who tended the flower beds. The higher we went, the less likely we were to see anyone other than people like us — white families — in their Sunday clothes, families licking ice creams, shouting to one another, playing hide and seek around the statues.

When I imagine the scene now, this world seems faded, old fashioned and a little fantastical. White children, green grass, blond stone and the sun baking down on the folly, hardening it into reality. This was our civic church, it was the place that whites, especially Afrikaners like my father, were proud of. The Union Buildings represented the Afrikaner struggle for independence, and their triumph and separation from the British Empire. It was a bold building for a bold nation. It was a place celebrating the final compromise and peace between Boer and Briton; the West wing housed the English speaking politicians and administration, the East wing was for the Afrikaners, its foundation stone written in Dutch. Between the two the amphitheatre embraced both. In this snapshot from memory, the space is empty of black faces, an omission so obvious now, and yet on a shimmering summer’s day in 1969 this absence was not visible to me.

My father would have known about the women marching in 1956, but he never told me as we wandered up the same steps, climbed the same terraces, and sat in the same amphitheatre as the protestors. That was an event from another world which we did not incorporate into our own. In the way that things were then, apartheid was made visible not only in the benches we sat on, or the places we were, or were not allowed to go. It was also in the histories we told ourselves; both the stories and the silences. My father’s particular history told of the proud Boer General, the domination of the British Empire and the shame of the Boer War. He would never have considered the March of the Women as history that meant anything to him or to the whites in South Africa. We could roam the terraces, eat ice cream and admire the view. We appreciated the sound of the water from the fountains. Here high above the city we were gods and this was how things were. This was, it must have seemed to him, the way it would always be. He could never have thought then that the bravery of those dangerous women who marched on the Union Buildings that cold winter’s day would have a special place in South African history, and that their courage would be celebrated every year on Women’s Day, the 9th August.

A note on National Women’s Day in South Africa

The first national Women’s Day was celebrated in 1995, the year after the Democratic elections. August is also National Women’s month. While South Africa has a democratic constitution and the rights of women are enshrined in this document, and the government has passed numerous laws to promote and protect the equality of women, the reality is that life is still very difficult for the majority of South African women and girls today. Poverty, poorly paid domestic labour, low educational attainment, high unemployment, HIV Aids and domestic abuse are still issues that are not being properly addressed. Every year these issues are highlighted on National Women’s Day and the hope is, of course, that these will be tackled in a systematic way.

For more detail on this see Women in South Africa: Walking Several Paces Behind (2010) (Accessed 10/9/16)

Other reading

‘History of Women’s Struggle in South Africa’ in South African History Online: Towards a People’s History (Accessed 10/9/2016).

‘South Africa Celebrates the First National Women’s Day’ (1998) in South African History Online: Towards a People’s History (Accessed 10/9/2016).

History of the Union Buildings in South African History Online: Towards a People’s History (Accessed 10/9/2016.

Mulaudzi G., South Africa: Celebrating South African National Women’s Day (Accessed 10/9/2016).

Randeree, Bilal. (2009) ‘When you Strike a Woman you Strike a Rock’ (Accessed 10/9/2016).

Visual material for National Women’s Day in South Africa (Accessed 10/9/2016).

You have Struck a Rock : Women and Political Repression in South Africa (1980) : International Defence & Aid Fund for Southern Africa