Deb Hunter writes fiction as Hunter S. Jones, publishing as an indie author, as well as through MadeGlobal Publishing. She is a member of the prestigious Society of Authors founded by Lord Tennyson, Romance Writers of America (PAN member), Historical Writers’ Association, Society of Civil War Historians (US), Historical Novel Society, English Historical Fiction Authors, Atlanta Writers Club, Atlanta Writers Conference, and Rivendell Writers Colony which is associated with The University of the South. Originally from Chattanooga, Tennessee, she now lives in Atlanta, Georgia with her Scottish born husband. You can follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram among others.

Deb Hunter writes fiction as Hunter S. Jones, publishing as an indie author, as well as through MadeGlobal Publishing. She is a member of the prestigious Society of Authors founded by Lord Tennyson, Romance Writers of America (PAN member), Historical Writers’ Association, Society of Civil War Historians (US), Historical Novel Society, English Historical Fiction Authors, Atlanta Writers Club, Atlanta Writers Conference, and Rivendell Writers Colony which is associated with The University of the South. Originally from Chattanooga, Tennessee, she now lives in Atlanta, Georgia with her Scottish born husband. You can follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram among others.

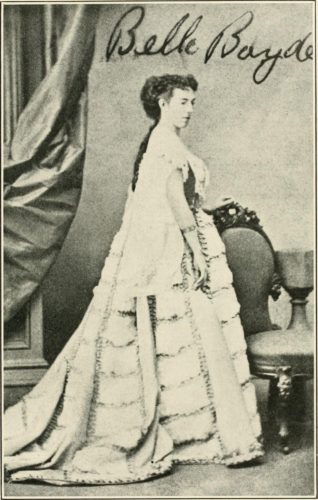

Maria Isabella “Belle” Boyd was one of the U.S. Civil War’s most famous spies. She was born in May 1844 in Martinsburg, Virginia, which is now the state of West Virginia, to a prosperous family with strong Southern allegiances. During the Civil War, her father was a soldier under Confederate Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in the Stonewall Brigade. During the war, at least three other members of her family were convicted of being Confederate spies, even though her home state severed from Virginia in order to remain a part of the Union.

Belle began her career as “La Belle Rebelle,” at age 17. Following a skirmish at Falling Waters, West Virginia on July 2, 1861, Union troops occupied Martinsburg. On July 4, Belle Boyd shot and killed a drunken Union soldier. Belle wrote in her post-war memoirs that he “addressed my mother and myself in language as offensive as it is possible to conceive. I could stand it no longer…we ladies were obliged to go armed in order to protect ourselves as best we might from insult and outrage.” She did not suffer any reprisal for this action. She recorded, “the commanding officer…inquired into all the circumstances with strict impartiality, and finally said I had ‘done perfectly right.'”

By early 1862 her activities were well known to the Union Army and the press, who dubbed her “the Siren of the Shenandoah,” “the Rebel Joan of Arc,” and “Amazon of Secessia.” In fact, the New York Tribune described her whole attire as, “a gold palmetto tree pin beneath her beautiful chin, a Rebel soldier’s belt around her waist, and a velvet band across her forehead with the seven stars of the Confederacy shedding their pale light there from…the only additional ornament she required to render herself perfectly beautiful was a Yankee halter noose encircling her neck.”

Belle Boyd made good use her layers of petticoats and crinoline, along with her feminine wiles, and became adapt at smuggling. She recruited other Southern women in this endeavor, teaching them to hide weaponry, such as muskets and sabers, under their hoop skirts. One example being the morning Union troops of the 28th Pennsylvania Regiment awoke near Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia to find 200 sabers, 400 pistols, 1,400 muskets, and cavalry equipment for their men had disappeared following their dalliances during the night.

Boyd frequented the Union camps, gathering information, and acting as a courier, too. According to her highly embellished memoirs she managed to eavesdrop on a Council of War while visiting relatives whose home in Front Royal, Virginia was being used as a Union headquarters. Learning that Union Major General Nathaniel Banks’ forces had been ordered to march, she rode fifteen miles to inform General “Stonewall” Jackson who was nearby in the Shenandoah Valley and returned home under cover of darkness.

Weeks later, on May 23, she realized Jackson was about to attack Front Royal, she ran onto the battlefield to provide the General with last minute information about the Union troops. Jackson’s aide, Lieutenant Henry Kyd Douglas, described seeing “the figure of a woman in white glide swiftly out of town…she seemed…to heed neither weeds nor fences, but waved a bonnet as she came on.” Boyd later wrote, “the Federal pickets…immediately fired upon me…my escape was most providential…rifle-balls flew thick and fast about me…so near my feet as to throw dust in my eyes…numerous bullets whistled by my ears, several actually pierced different parts of my clothing.” Jackson captured the town and acknowledged her contribution and her bravery in a personal note.

Boyd’s flirtations with Union officers, however, were her strongest source of influence. Contemporaries noted that “without being beautiful, she is very attractive…quite tall…a superb figure…and dressed with much taste.” On one occasion, she wooed a Northern soldier to whom, she wrote, “I am indebted for some very remarkable effusions, some withered flowers, and last, but not least, for a great deal of very important information…I must avow the flowers and the poetry were comparatively valueless in my eyes.” Boyd continued, “I allowed but one thought to keep possession of my mind—the thought that I was doing all a woman could do for her country’s cause.”

Boyd was arrested six or seven times; the records are misleading. She managed to avoid incarceration until July 29, 1862, when she was finally imprisoned in Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C. She was released after a month as part of a prisoner exchange, but was arrested again in July 1863. Boyd was not a model inmate. She waved Confederate flags from her window, she sang Dixie, and devised a unique method of communicating with supporters outside. Her contacts would shoot a rubber ball into her cell with a bow and arrow. In return, Boyd would sew messages inside the ball.

In December 1863 she was released and banished to the South. Instead, she sailed for England on May 8, 1864 and was arrested as a Confederate courier. She finally escaped to Canada with the help of a Union naval officer, Lieutenant Sam Hardinge, and eventually made her way to England where she and Hardinge were married on August 25, 1864.

“Her big claim to fame is how she literally ran into the oncoming fire to warn Stonewall Jackson about the Union forces that were converging,” Abbott says. “Stonewall might have already had that information, but she confirmed it for him. She rewrote her narrative however she saw fit in the moment, which I thought was one of her more charming characteristics. She had an endless imagination. No matter what she was doing, she could find a way to sort of spin it for herself. I love that when she married her first husband, the Yankee, during the war,” says author Karen Abbott of Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War.

Boyd remained in England for two years writing her memoirs, Belle Boyd in Camp and Prison. While there, she achieved success and acclaim on the stage. She returned to America in 1866, a widow and mother, where she continued her stage career and lectured on her war experiences. Her show was billed as The Perils of a Spy. Belle Boyd become known as the “Cleopatra of the Secession.”

With all this Victorian romanticization, she, was able to turn herself into a celebrity of the Lost Cause. In the late 1860s, she began billing herself as “Belle Boyd, of Virginia” as she improvised tales from her 1865 memoir, Belle Boyd in Camp and Prison. She performed in Washington, D.C., and New Orleans; sometimes she would even ride onstage on a horse. In 1870, she checked into an insane asylum because her mind “gave away,” and she avoided the spotlight for fifteen years. Women pretending to be Belle Boyd appeared all over the United States, in Martinsburg, in Philadelphia, in Atlanta, and in Corsicana, Texas.

The actual Bell Boyd returned to the stage in 1886, opening a one-woman touring show, The Perils of a Spy that also played in Northern states. The story centered on her most famous moment—the day she rode through the front lines at the Battle of Front Row to breathlessly inform Stonewall Jackson of the enemy’s strategy.

In 1869, she married an Englishman, John Swainston Hammond, who had fought for the Union Army. Sixteen years and four children later, in November 1884, the couple divorced. Two months following the break-up, Belle married Nathaniel High, Jr., an actor seventeen years her junior.

Belle Boyd lived her life colorfully and dangerously. Yet, she died in poverty of a heart attack on June 11, 1900 while on tour in Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin. She is buried there, in Spring Grove Cemetery.

Sources

Belle Boyd’s autobiography, Belle Boyd, In Camp and Prison, 1865.

Spies of the Confederacy by John Bakeless, published by J. B. Lippincott Co., 1970.

The War the Women Lived by Walter Sullivan, published by J.S. Sanders & Co.,1995.

Spies and Spymasters of the Civil War by Donald E. Markle, published by Hippocrene Books, 1994.

Mighty Stonewall by Frank E. Vandiver, published by Texas and A&M Press, 2010.

The Secret War for the Union by Edwin C. Fishel, published by Houghton Mifflin Co., 1997.

Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War, Karen Abbott, published by Harper, 2014.